HKU's Giorgio Biancorosso Examines the Combinatorial Practice at the Heart of Wong Kar-wai's Cinema

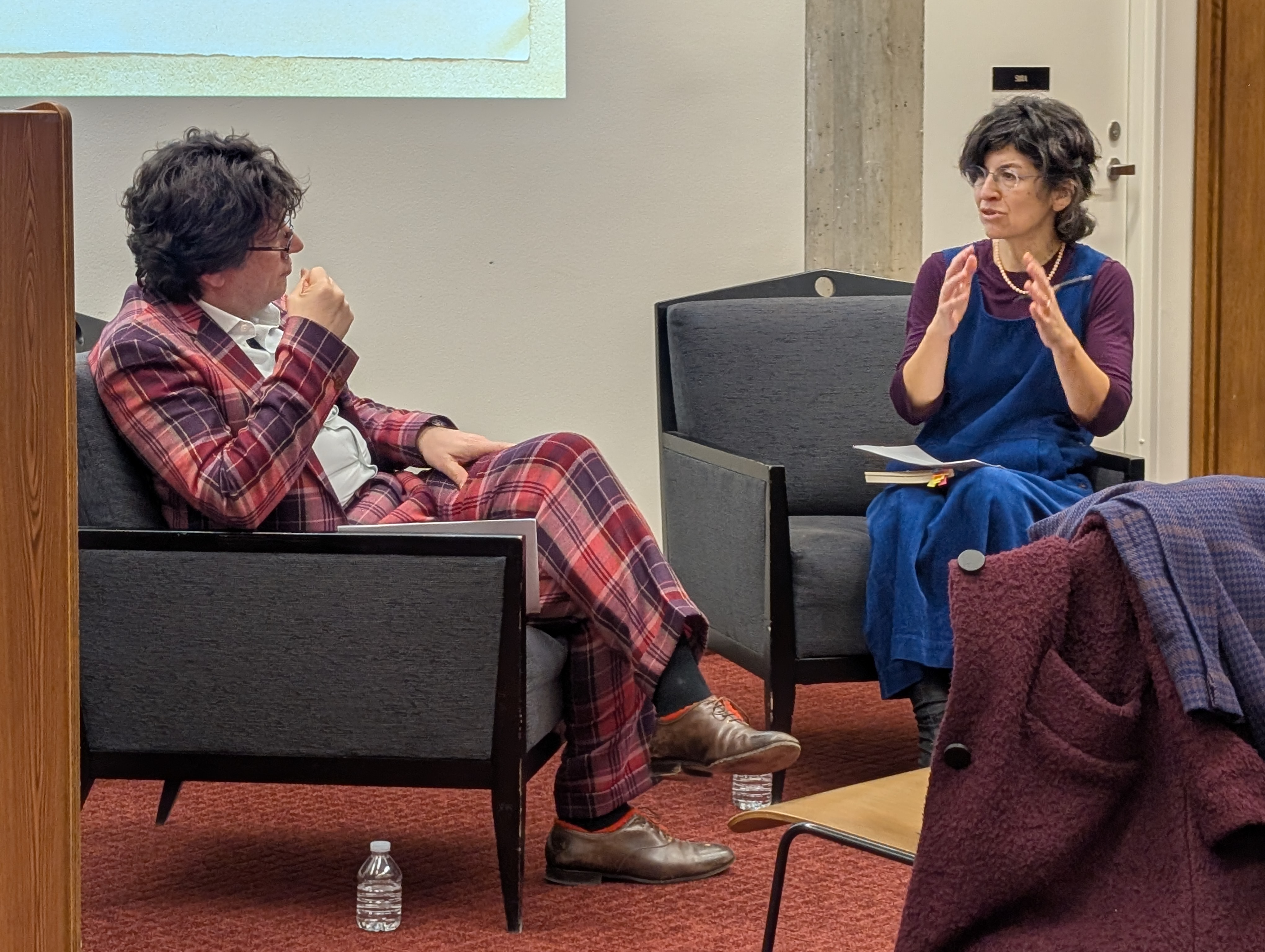

On February 27, 2025 the Center for East Asian Studies at the University of Chicago hosted Giorgio Biancorosso, Professor of Music at the University of Hong Kong, to discuss his new book, Remixing Wong Kar-wai: Music, Bricolage, and the Aesthetics of Oblivion (Duke, 2025) in conversation with Professor Paola Iovene from the University of Chicago.

Biancorosso began the event by providing a brief introduction of his arguments, before entering into conversation with Professor Iovene. In his words, his book “does what the title says it does”, “remixing” the films of Wong Kar Wai in order to “bend and […] forget” them, just as he claims Wong does to the music he retools in his films’ complex soundtracks. Biancorosso claims that Wong’s plethora of references are not an attempt to draw on memories but instead “defamiliarize” viewers with the “very music and image [they] thought [they] were familiar with.” While most critics might focus on the act of remembering, Biancorosso instead highlights the act of forgetting inherent in this remixing.

He demonstrated these ideas using a clip from the end of Wong’s 1990 film Days of Being Wild, a long unedited shot where a gambler played by Tony Leung gets dressed. While the music accompanying this scene has a long and varied history, “the resulting bricolage defies reproducibility” and “seals the music to the gambler, and with it the film.” Whatever the original context of the music Wong draws from, by putting it into his film Wong creates an entirely new narrative for it.

Biancorosso describes his methods in Remixing Wong Kar Wai as an experiment in “vintage scholarship” that is, working from a perspective that he calls “pre-post-structuralist criticism”. In the case of Wong, Biancorosso explains that most scholars tend to point out his myriad of intertextual references, an act he attributes to the scholarly desire to become “co-creators” of the work. Instead, he believes the role of the scholar is to “know everything about Wong’s original sources, only to then [be able to point out] that it doesn’t matter”. Instead of looking at the relationship between “text and other text”, Biancorosso examines the relationship between “text and world”, focusing on how bringing together myriad sources allows Wong to “build” a cogent world.

Biancorosso ties this interest in “worldbuilding” with the idea of “bricolage”, that is, the putting together of existing materials to create a new whole. The idea of bricolage, he says, particularly fits the “fiction film”, because “bricolage is built into the post production process as a matter of course”—in other words, the director must always put together existing material as a part of the editing process. Wong’s technique of bringing in a variety of existing music sources serves as a natural corollary of this existing procedure. Biancorosso explains that “world making is implicit in bricolage”, as the “genuine bricoleur is interested in enacting something in the here and now of the filmgoing experience” as opposed to focusing on the past. Once a piece of music is placed into the context of a Wong Kar Wai film, his remixing and bricolage divorces the song from its original context and adds it to an entirely new world, making him its new “owner in a metaphorical sense”.

At the same time, Biancorosso takes care not to “romanticize the process of filmmaking” or put too much stock into the idea of the genius auteur. While he calls Wong a “curator”, he also claims that his choices of music are tied not to “conscious narrative design” but to “expediency”, as Wong simply takes pieces of music he likes from other media (or other films) as a way of more effectively evoking a desired effect. Because of his nature as a “bricoleur”, Biancorosso decenters the idea of the author, as the inspirations and individuals involved in the creation of the film easily transcend the director as a single, all-encompassing controlling agency.

Giorgia Biancorosso is also the author of Situated Listening: The Sound of Absorption in Classical Cinema (Oxford, 2016) and the co-founder and editor of the journal SSS (Sound Stage Screen). For the past year, he has been Luce East Asian Fellow in musicology at the National Humanities Center in North Carolina. In addition to his scholarly work, Professor Biancorosso is active as a programmer, dramaturg, and director.

This event was a part of the series East Asia by the Book! CEAS Author Talks series, which showcases CEAS faculty, alumni, and special guests who provide author talks and book launches as a way to engage the broader community in conversations regarding key scholarship on East Asia.

The next East Asia by the Book! CEAS Author Talks event will take place May 15, 2025 and feature "Coercive Commerce: Global Capital and Imperial Governance at the End of the Qing Empire" by Stacie Kent, Assistant Professor of Global History and International Studies at Boston College.

Written by Lena Birkholz

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO